First of all, we are not ladies that lunch. Let’s set things straight. Given the choice we definitely brunch. Madelines, given. But also crusty, salted croissants with chocolat centers; belgian waffles with honey vanilla syrup and macerated strawberries; poached eggs with wilted greens and slabs of rustic toast. . . porcelain bowls of coffee, pots of marshmallow cocoa, and sensible mugs of black Irish tea.

Nor are we (solely) interested in what editor Christopher Pendergrast calls the “cakes-and strawberries version of Proust. . . the equivalent of the tea-party image of Jane Austen’s world favoured by a certain class of Janeties.” Apologies in advance for being cheeky, but we are no Jane Austen Book Club. Let’s face it–we’ve all been burned by book clubs before.

We are, to borrow the young Marcel Proust’s answers on the infamous questionaire , The Real Life Proustian Heroines: women of genius leading ordinary lives. We are, among us, mothers, wives, dog-owners and recovering academics. We notate margins when we read and have favorite writing instruments. We check the mail for letter pressed invitations sent with hand-canceled postage stamps. Such things cannot be helped. But we are thirsty for conversations written on the back of coffee cup sleeves. We are women who have committed to carrying a dog-eared paperback in our diaper bags, jet-blue carry-ons, and notebook-filled glove compartments.

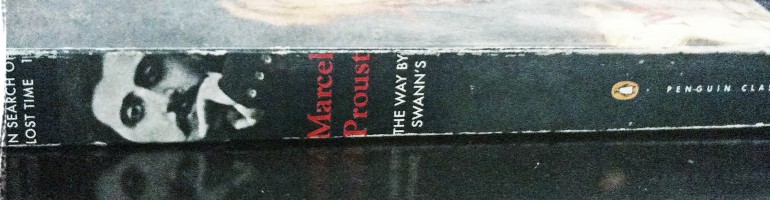

And so it works like this: we are beginning at the beginning and when we get to the end we’ll stop. We have chosen Penguin’s new translations of Proust edited by Pendergrast because quite simply, we agree: “there seems to be no good reason for making English Proust more ‘reader-friendly’ than French Proust.” We are willing (as followers of Woolf, Joyce and Didion) to do the work of reading page by page, following Proust who drags the reader

where hitherto the novel did not typically go, insisting that what is deemed insignificant by the latter may hold the key to the meaning of a life.

But beware: we will drag Proust into our daily, ordinary lives and see what we can bring to the page. Our commitment is simply thus: page by page.

Our posts may be on a line, a word, a Proustian thought; they may be daily, or perhaps obsessively on the hour, or when the words have reached their humming capacity: quarterly. We will take The Way By Swann’s and see where it leads us.

And why not? Especially when the first volume’s translator Lydia Davis promises:

the better acquainted we become with this book the more it yeilds. Given its richness and resilience, Proust’s work may be enjoyed on every level and in every form–as quotation, as excerpt, as compendium, even as movie and comic book–but in the end it is best appreciated in the way it was meant to be experienced, in the full, slow reading and rereading of every word, in utter submission to Proust’s subtle psychological analyses, his precise portraits, his compassionate humour, his richly coloured and lyrical landscapes, his extended digressions, his architectonic sentences, his symphonic structures, his perfect formal designs.

Such promises make one vertiginous indeed–but enough, this is no dissertation. This is a conversation among friends engaged in the pursuit of everyday magic.

This is beauty. And truth. And wallpaper. Wallpaper that covers your favorite, secret spaces. The seams don’t always match up, and way way high near the dusty vent a corner is pealing, but it’s perfect that way: lived in, real and adored.

Yes, but let’s not mix it up with “The Yellow Wallpaper,” which, quite frankly, is all I can think about when I stare at the faded floral rug in my therapist’s office. Sometimes I fear I’ll have to send an SOS text from her waiting room and wait for the lot of you to rescue me.

Pingback: my mother’s voice, my father’s eye, and my other body: the sound of deaf photographs « Sounding Out!